Welcome to this week’s A-B-C of Writing True Stories newsletter.

This week I want to look at the main building block of writing narrative nonfiction: the scene.

Facts and details

It’s true that nonfiction is made up of facts and details. That’s what a book like In Cold Blood has in common with an encyclopaedia.

But what makes them different? It’s storytelling. And what’s the basic unit of storytelling? I believe it’s the scene.

I think we can learn a lot from cinema and TV when breaking down our true story. Scenes are the lifeblood of great storytelling.

Once we have our research done, we can begin constructing great, cinematic, dramatic scenes that pull the reader in.

Timeline

It can be helpful to know the timeline of events of your story. As you research, file each nugget of information under the relevant place in the timeline.

As you build this up, you should start to see the key events that push the story along. These are your scenes.

You should be able to see why these scenes are important. Why and how do they push the story along? What changes as a result of a particular scene?

If the scene does not fulfil either function, then question why it’s in your book. Not every detail — however interesting — needs to be included, especially if it slows down the narrative. You run the risk of writing an encyclopaedia rather than a story otherwise.

Fill in the gaps later

If you know the general sweep of your scene, but you haven’t yet finished your research, block out what you do know. You can go back and fill in the gaps as you unearth the verifiable facts.

Writing your book will be a continual process of sweeping through your manuscript adding to what is already there: details of the weather on that day in 1953, the food served at that dinner in 1899, or the injuries sustained by the victim of that murder in 1974.

Don’t forget the senses

The best scenes are those that engage all the senses. Research details that will help you describe not only what something looked like, but also what could be smelt, heard or felt.

For example, looking at weather reports is one way of bringing verisimilitude to your writing.

Spotting potential in skimpy resources

Scenes will not necessarily leap out at you. You sometimes have to mine quite deeply to find the rich seam of material.

It might be data hidden in a century-old census return, or the shadowy figures lurking in a water-damaged sepia photograph.

This part of the job is like being both a journalist and a dramatist — pinning down the facts before exploring how they can be turned into compelling drama.

Scene from The Jigsaw Murders

I will give you an example from my own book, The Jigsaw Murders.

In late 1935, Dr Buck Ruxton, the Lancaster GP, was facing trial for murdering and dismembering his wife Isabella and children’s nanny Mary Rogerson. Ruxton wanted to hire a hot-shot lawyer to defend him. He had his sights on Norman Birkett, the hottest of all barristers in England at the time. Birkett would not come cheap.

At this point in the story, my research showed that Ruxton’s Lancaster solicitor, Fred Gardner, organised an auction to sell off the doctor’s furniture and personal possessions.

Previous accounts of the Ruxton case mention the auction, but only in passing and references are no more than a line or two. No other writer before had bothered to dig very deeply.

As my goal was to write the richest account possible, I knew this could make for a really strong, cinematic scene. I felt it would add texture to the story and transport the reader back to 1935 Lancashire.

So I had to turn ‘an auction was held to sell Ruxton’s furniture and personal belongings’ into a vivid scene.

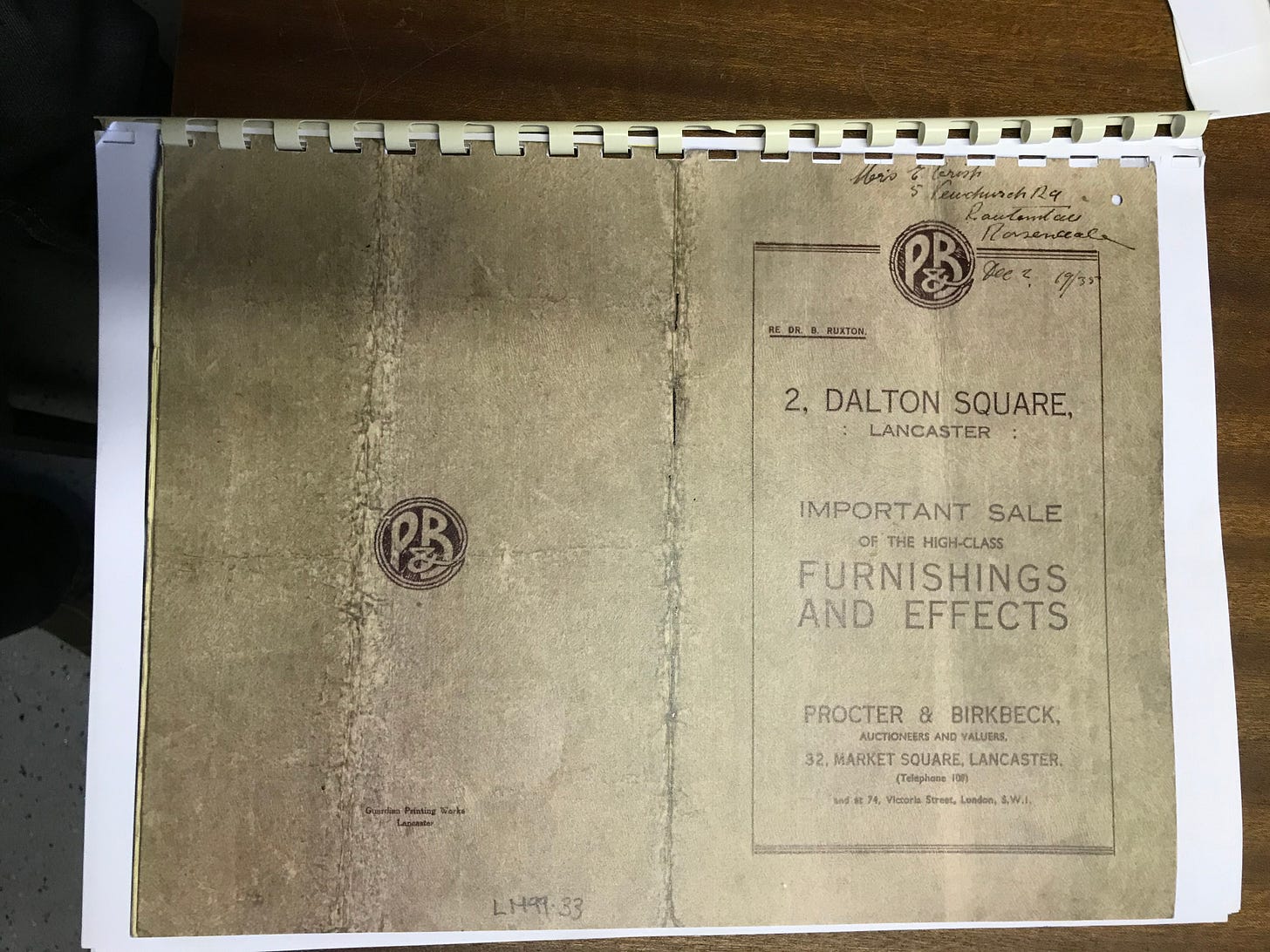

At Lancaster City Museum I found a copy of the sales catalogue produced by auctioneers Procter and Birkbeck. This detailed every item being offered for sale. It told me the dates and times of open-house viewings at Ruxton’s house on Dalton Square (also the scene of the murders). The woman whose catalogue it was had scribbled her name and made notes throughout of items she was interested in.

So, armed with this information, I did the following:

Researched old copies of the Lancaster Guardian and Morecambe Visitor for details about Procter and Birkbeck, including information about Thomas Birkbeck, the auctioneer who led the sale.

Researched Mrs Parish (the owner of the catalogue) using her marriage record.

Sourced a press photograph of the actual auction to enable me to describe the scene.

Also found a press photo of the open-house viewings at Ruxton’s house, again to help set the scene and describe events.

Visited the hall in Lancaster where the auction took place.

All of the above took a long time. All this effort resulted in around 400 words. Not a lot you might think, but that was what it took to produce a rich and textured account of the auction. Extrapolate that across all the scenes in the book and you get a sense of why it took almost four years to write the book.

But I think your true story will be so much richer for this sort of diligent journalistic approach.

Here’s (some) of the scene I wrote:

Kinetic writing

As you’re writing these scenes it’s worth keeping in mind that you have the same aim as a novelist, even though you are telling a true story.

Remember to keep your writing vivid and kinetic.

In the opening of Seabiscuit, Laura Hillenbrand introduces one of her main characters: Charles Howard, the businessman who buys the eponymous racehorse. Howard was a former bicycle salesman turned seller of motorcars. He was known for his energy.

Hillenbrand could have described Howard in a single line and moved her story on, something along the lines of: ‘Charles Howard was full of energy, a natural leader’.

But take a look at how Hillenbrand, a brilliant writer, chose to introduce the reader to one of the central characters of her story.

Charles Howard had the feel of a gigantic onrushing machine: You had to either climb on or leap out of the way. He would sweep into the room, working a cigarette in his fingers, and people would trail him like a pilot fish… (Seabiscuit: Chapter one, page 3)

It’s always worth consulting the source notes at the end of any narrative nonfiction book to see how much work the author has done. One look at Laura Hillenbrand’s sources will have you doffing your hat out of respect.

I hope this newsletter has inspired you to go the extra mile in your research and to make your scenes come alive, rather than just writing a flat statement of what happened.

Questions for you to take away:

In each newsletter I will give you some questions to ponder. Consider it homework!

Can you see the key events of your story that you can develop as scenes? If you can’t, you need to dig deeper.

Is there enough source material to help you recreate your scenes? If not, do some more research.

Have you engaged all the senses in your scene? Is your writing vivid and kinetic?

Does your scene move the story along? Do things change as a result?

Reading recommendations:

Seabiscuit by Laura Hillenbrand

Devil in the White City by Erik Larson

The Suspicions of Mr Whicher by Kate Summerscale

In Cold Blood by Truman Capote

All of these are brilliantly researched (Capote’s is slightly disputed!) and beautifully written.

Also, you might like to take a look at my book, The Jigsaw Murders.